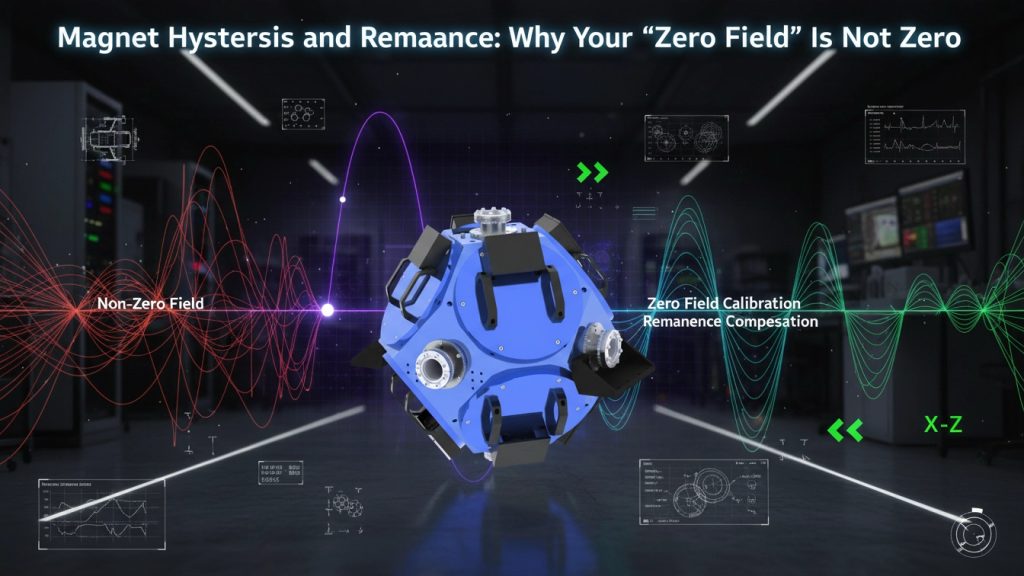

In many physics experiments, researchers assume that setting the current to zero means the magnetic field is zero.

Unfortunately, this assumption is often wrong.

Magnet hysteresis and remanence are common sources of unexpected and confusing experimental results.

This article explains why “zero field” is rarely zero, how hysteresis affects measurements, and what can be done in practice.

1. The Hidden Problem Behind “Strange” Experimental Data

Researchers often report:

- Offset signals at zero field

- Non-symmetric field sweeps

- Irreproducible baseline measurements

These effects are frequently blamed on samples or instruments.

In reality, the magnetic field itself is often the culprit.

2. What Is Magnetic Hysteresis?

Magnetic hysteresis means that the magnetic field depends on its history.

When current increases and then decreases, the magnetic flux does not follow the same path.

As a result:

- The field at zero current is not zero

- The field depends on the sweep direction

This behavior is intrinsic to ferromagnetic materials.

3. Remanence: The Residual Field You Did Not Ask For

Remanence is the magnetic field that remains after the applied current returns to zero.

It originates from:

- Magnet core materials

- Pole pieces and yokes

- Nearby ferromagnetic structures

Even small remanent fields can affect sensitive measurements.

4. Why “Zero Field” Is Experimentally Dangerous

Many experiments rely on accurate zero-field conditions.

Examples include:

- Hall measurements

- Magnetotransport studies

- Low-field magnetic transitions

If remanence is ignored, zero-field data becomes unreliable.

This leads to systematic errors that are hard to diagnose.

5. How Pole Materials and Geometry Affect Remanence

Remanence is not only a material property.

It is also influenced by:

- Pole face material

- Pole shape and size

- Magnetic circuit symmetry

Poorly designed pole geometries increase hysteresis effects.

This directly impacts field repeatability.

6. Practical Demagnetization Strategies

Field Cycling

Applying decreasing alternating fields can reduce remanence.

This process gradually randomizes magnetic domains.

Reverse Field Sweeps

Sweeping the field past zero in both directions helps stabilize the magnetic state.

Controlled Ramping Profiles

Slow, symmetric ramping minimizes hysteresis-related artifacts.

These methods should be part of standard measurement protocols.

7. Zero-Field Calibration and Verification

Zero field should never be assumed.

Good practice includes:

- Measuring residual field with a Hall probe

- Recording remanence after each sweep

- Repeating demagnetization when needed

Zero-field calibration is an experimental requirement, not a luxury.

8. Engineering Solutions for Managing Hysteresis

Effective hysteresis control requires system-level design.

This includes:

- Carefully selected electromagnet materials

- Optimized pole geometry

- Repeatable current ramping control

- Software-assisted sweep strategies

Cryomagtech systems are designed to support reproducible magnetic field conditions.

9. Why Software and Control Strategy Matter

Hardware alone is not enough.

Control software plays a key role by:

- Enforcing repeatable sweep profiles

- Automating demagnetization routines

- Logging magnetic history

This transforms hysteresis from a mystery into a manageable parameter.

References

- Wikipedia – Magnetic hysteresis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_hysteresis - IEEE – Magnetic materials and hysteresis behavior

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org

Final Thoughts

If your experiment depends on zero field, you must define what “zero” means.

Ignoring hysteresis does not eliminate it.

It only hides the problem.

Understanding remanence is the first step toward reproducible magnetic experiments.